Growth vs. Value: Waiting for GODOT

Growth vs. Value: Waiting for GODOT

By Gautam Dhingra, PhD, CFA Posted In: Drivers of Value, Economics, Equity Investments, Future States, Portfolio ManagementIs it time to start selling growth stocks and buying value stocks?

After the formers’ long run of outperformance, value stocks must be due for an upswing. Right?

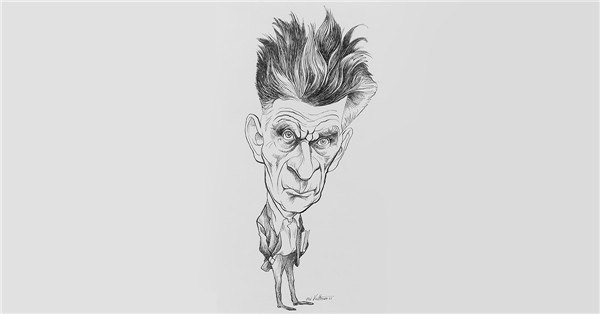

These questions are on the minds of countless investors, so at the risk of making Samuel Beckett, winner of the 1969 Nobel Prize in literature, turn in his grave, I’d characterize our current predicament as “Waiting for GODOT (Growth’s Overdue Decline over Time).”

Growth vs. Value Performance: January 2009–July 2018

Since the end of the financial crisis, growth stocks have outperformed their value counterparts by 144%. But maybe that’s misleading because of the selective and short-term nature of the time frame.

If we extend the measurement period back, say, to the bursting of the tech bubble in March 2000, a different view of the relative performance of value and growth stocks emerges.

Growth vs. Value Performance: March 2000–July 2018

While historical return charts like the above are compelling, they don’t offer much insight into the likely future returns of value and growth stocks. Instead, we’re better off looking at a valuation chart. The graphic below depicts the forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of growth stocks and value stocks using the Thomson Reuters Eikon database, with data extending back to January 2002.

Forward P/E Ratio of Growth and Value Stocks

What does this chart tell us? For starters, it shows how unusual early 2009 was in terms of relative valuation. Growth stocks were selling at valuations that were roughly comparable to those of value stocks. This was quite unusual since growth stocks have higher expected earnings and sales growth rates.

Indeed, since 2009 growth stocks have lived up to their moniker and generated higher earnings growth.

Earnings Growth since the Financial Crisis, January 2009–July 2018

Russell 1000 Growth Index: 84%

Russell 1000 Value Index: 30%

This demonstrates that their outperformance since January 2009 is not a fluke, but is the result of two factors in particular:

Growth stocks’ low valuation at the beginning of the period.Their stronger earnings growth.

But an important question remains: Since growth stocks sell at a forward P/E multiple of 20.9 compared to 14.4 for value stocks, is the size of the valuation gap justified?

To answer this question, we constructed a two-stage dividend discount model based on the premise that there are two stages in a company’s life: Stage 1, wherein the firm retains most of its earnings and uses them to fuel an above-average growth rate; and Stage 2, when the company pays out a greater portion of its earnings as dividends and its return on equity converges to its cost of equity, resulting in a slower growth rate.

So what’s the purpose of this valuation exercise? We want to make a judgment only about the relative merits of growth and value stocks rather than the absolute valuation level of the market as a whole. By narrowing our goal, we can first infer the implicit assumptions in the overall market’s valuation and then modify those assumptions for the universes of growth and value stocks to determine their fair relative valuations.

The table below summarizes the assumptions. We lay out the rationales behind them in the Appendix. The last two rows of the table show the estimate of fair (or expected) P/E ratio in light of these assumptions and its comparison with the actual P/E ratio.

By comparing the estimated fair forward P/E ratio with the actual forward P/E ratios, we find that growth stocks look overvalued relative to value stocks even after taking their superior growth rate into account.

Conclusion

Although a significant proportion of growth stocks’ recent outperformance is justified, there is a legitimate case for favoring value stocks over growth stocks at this time.

Put another way, unlike in the Beckett play, when it comes to the stock market, GODOT won’t keep us waiting forever.

Appendix

The P/E valuation equation implied by the two-stage dividend discount model is reproduced below, courtesy of Aswath Damodaran of New York University.

The Stage 1 growth rate assumption is derived from the median I/B/E/S long-term earnings growth estimates for the Russell 1000, Russell 1000 Growth, and Russell 1000 Value indexes going back to 2002 from the Eikon database.

The dividend payout ratio for Stage 1 is based on current data as of July 2018. For Stage 2, the ratio is logically raised above the Stage 1 ratio. The exact number, however, is simply a judgment on our part.

Cost of equity is derived by combining the risk-free rate of 2.9% based on 10-year Treasury bond yield and an equity risk premium of 5.1% as calculated by Damodaran.

The Stage 2 growth rate assumes that State 2 return on equity converges to the cost of equity and then multiplies it by the earnings retention ratio to derive the expected growth rate.

The length of Stage 1 is a balancing figure that allows us to equate the estimated fair P/E ratio of the broad market to be roughly equal to the actual P/E ratio of the broad market.

There is clearly room for judgment and disagreement about our assumptions. Moreover, the model is quite sensitive to changes in certain assumptions. Nevertheless, we believe this exercise will help us make more informed decision about value vs. growth stocks rather than simply guessing based on past performance.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: Edmund S. Valtman, courtesy of the US Library of Congress